Everything I Wish I Knew About Hiring

Hiring for a startup is an important lift - treat it like one.

This is a bit of a different post from me, but I thought it was important to share my thoughts on the hiring process with some of the startups I work with. When hiring people to grow my startup, I naturally made some mistakes, assuming it was easy. Most of the sections in this article could apply to any startup, but some are geared more toward early-stage companies that might be scaling from a handful of individuals to their first growth phase as a team (~10-20 individuals).

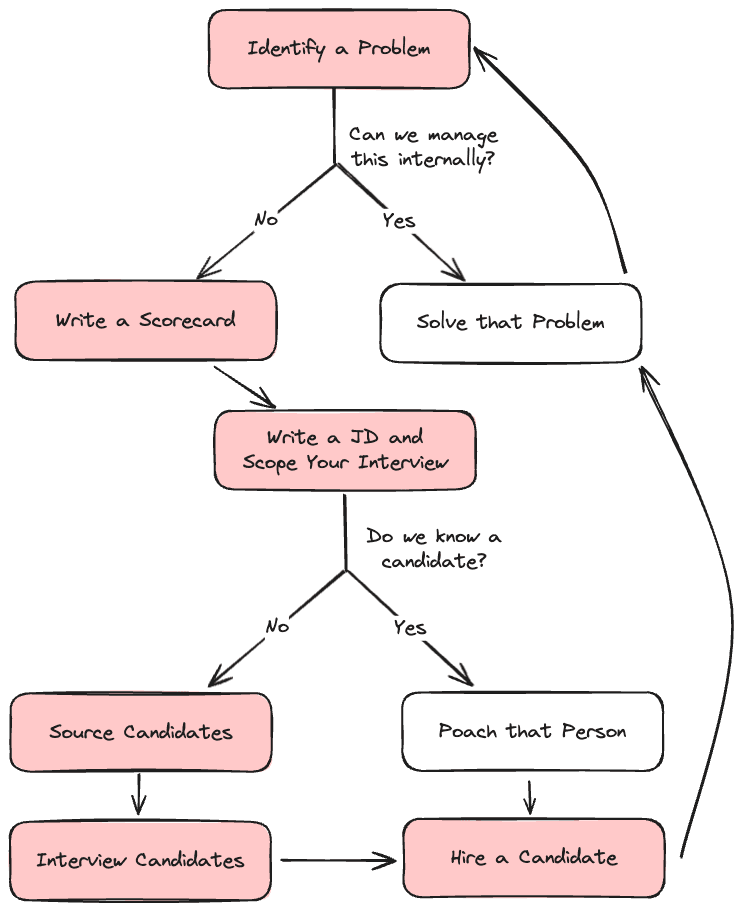

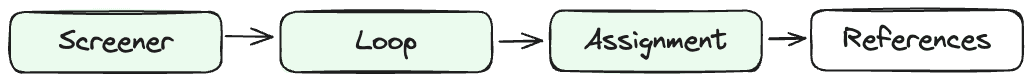

I’m going to break down each section, but effectively, the process for hiring is as follows:

We will be specifically reviewing the parts highlighted in red.

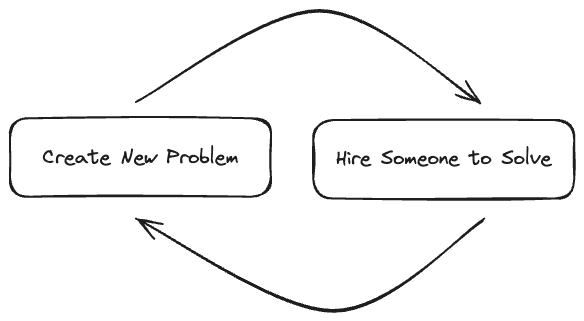

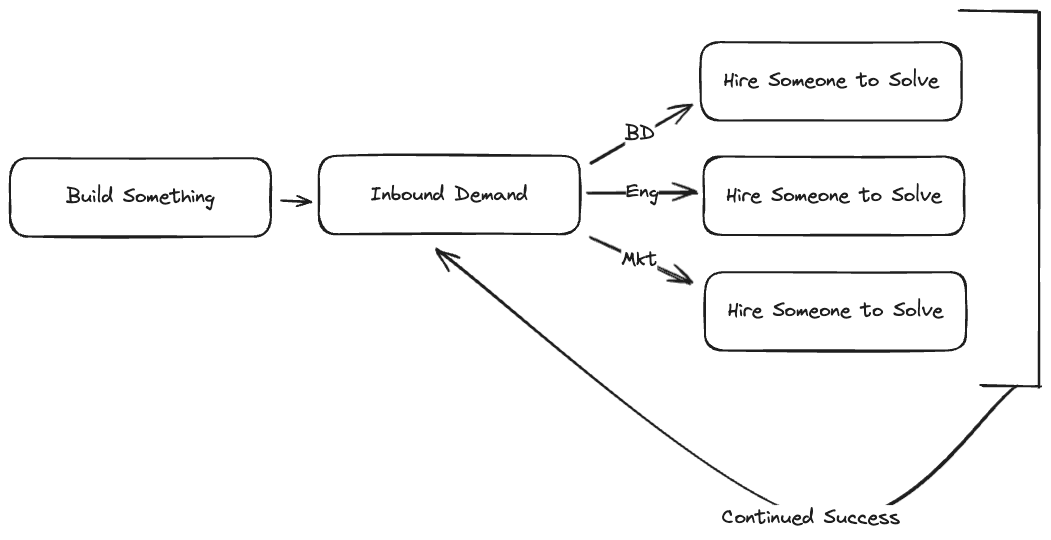

As an early founder, your first job is to do everything. This includes product, engineering, BD, marketing, selling, and negotiating. Now that we’ve established that, your next job is to identify scaling issues in your organization based on an actual need instead of a perceived problem. It’s very easy to say you need to hire for something, when in reality, it’s something you can solve yourself or not a legitimate problem the organization is facing:

Problems should come from success, or being on the brink of success rather than being invented by some intellectual quest. You need an internal way to validate success to justify hiring someone. This could include KPIs that you set based on product adoption, or even closing contracts and not having the resources to handle an increase in business that you’re generating (with good margins, of course):

After affirming, “Yes, we have an actual problem,” leaders typically draft a job description. This is a great way to waste time and potentially not find the candidate you’re looking for. Instead, return to the identified problem and draft a scorecard.

Note: much of my process is inspired by The Who Method.

A scorecard consists of outcomes and personality traits you’re optimizing for when considering opening up a role at your organization. There’s no ‘correct’ way to create a scorecard, and it doesn’t necessarily have to have a template. It can exist purely as a list you jot down in your notes or an email somewhere.

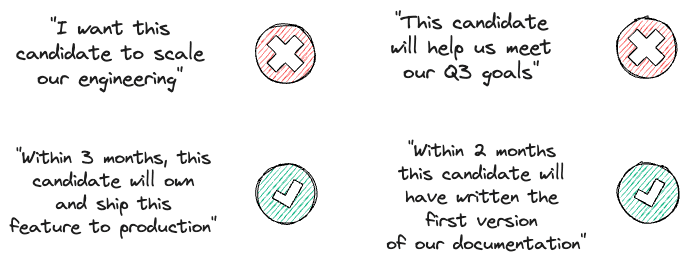

One way to start a scorecard is by listing and defining five immediate things you want this candidate to do. When thinking about these tasks, define them similarly to key results or key performance indicators with specificity and outcomes in mind:

If the requirements you write feel too loose to you, it’s because they are. In addition to those outcomes, write several traits you feel this candidate should possess when working on your team. This helps with eventually writing the job description and helps filter any inbound candidates based on your initial screener with them. These traits could include things like: “overly communicative,” or “individual contributor”.

By writing a scorecard, you might find the role begins to change based on the outcomes you’ve outlined. What originally started as a full-stack developer might be a developer relations specialist, or a backend engineer might be a product engineer, or even an operations lead might be a chief of staff. That’s why it’s important to draft a scorecard before a job description: you narrow in on what you want to hire for.

Now we can write the job description. Your job description should consist of five points:

An Introduction

This is where you’re not just describing the company and what it does, but selling the company. You’re a startup, not a worldwide phenomenon – and a candidate is taking equally if not more risk and opportunity cost by joining you than you are on them. Take four to five sentences to describe your company’s vision, what it produces, and why someone would want to work there. Talk about how you want to change the world and the type of individuals you want along for the journey. Don’t write a book, and get to the point.

A Set of Responsibilities

These should be heavily based on the outcomes you’ve defined in the scorecard earlier. Define at least five of these, but include no more than seven; these typically evolve after hiring a candidate. Be sure to scope these down as much as possible, similar to the scorecard. A candidate must read these and feel comfortable knowing exactly what they’re signing up for when they apply to work for your company.

A Set of Qualifications

These qualifications should be the necessary minimum to meet those responsibilities. Unless you want to spend an eternity hunting for a unicorn that would have an extremely narrow set of qualifications, make sure these are reasonable relative to those outcomes and responsibilities. Again, define at least five, but include no more than seven.

Bonuses

These are things added to the job description that aren’t necessary for candidates to have, but would increase their chances of being selected for the role. You can base these on abilities or some of the traits you’ve outlined earlier. For example, if you put “self-starter” as a trait in your scorecard, you might have “previous experience at a startup” as one of these bonuses, or “contributed to open-source software” if you’re an open-source software company.

Outro

Use this section for any odds and ends you wish to include in your job description. This could include notes about vacation policy, benefits, company culture, etc.

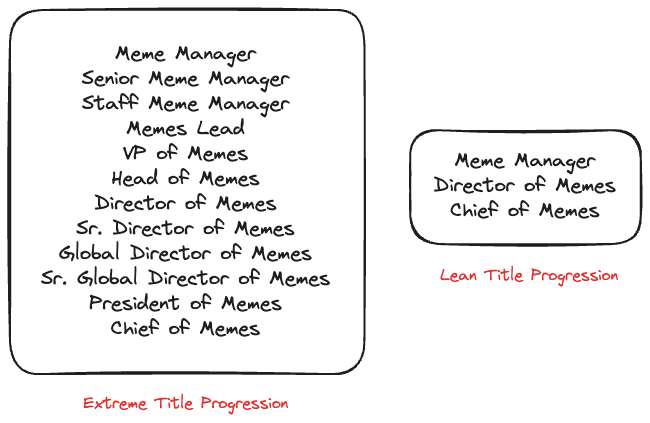

Now that we have that out of the way, you might ask yourself “but what about title and compensation?” Let’s have an honest conversation about titles. You may or may not be at the point of defining strict leveling at your organization (if you’re early, this is a distraction), but you’re going to have to make a few decisions based on your philosophy, which will impact your candidate pool (and be hard to adjust later):

What is your philosophy around titles against the amount of experience a candidate has?

Do you pay based on region if you’re a remote company, or do you have salary bands?

How do you weigh equity versus salary at your current stage and money raised?

For example, your philosophy about titles could be either lean or extreme, depending on how you want your organization to evolve.

These three questions will help you find the answers you need to think about the role’s title and compensation. Remember, compensation can always be discretionally adjusted - it’s good to have a set schedule for evaluations, but it’s ultimately up to you as a founder to set this. There are plenty of tools, such as Pave or Carta, that can help you benchmark compensation.

Defining a role is fun; sourcing, interviewing, and hiring are difficult.

You are the master of your destiny when it comes to talent. The more work you put into sourcing, the greater your outcomes. You’re not just going to post a job description, especially as an early startup, and have quality candidates breaking down your door to work for you. Sourcing can come from various places, but I recommend starting in your backyard, depending on the industry you’re coming from.

For example, if you’re a blockchain startup, you can source from any of the following areas:

Friends and allies - start by sourcing locally. This includes your entire network and your friend’s networks if they know of anyone on the market that might be a good fit for the role you posted. These candidates typically come pre-vetted through your own experience, or a referring party.

Investors - Typically, investors have a roster of talent that they keep and provide to portfolio companies as needs arise.

Conferences and hackathons - these act as great gatherings both for information and for hiring as well. You might discover talent at a hackathon or meet someone at a conference who is competent and looking for their next role at a new home.

Various corners of the internet - this includes both traditional and nontraditional means. For example, LinkedIn is always a simple place to look for candidates, but you can also try unique ways of vetting talent, such as looking at an engineer’s GitHub contributions, finding a marketer’s profile on Twitter, or even finding a business development lead active across multiple industry groups or forums.

Don’t waste your time with aggregators like Indeed—you’ll spend more time sifting through bad resumes than interviewing quality talent. I also wouldn’t recommend working with a recruiter until you’re at least a Series A company with a consistent hiring process.

There are two types of recruiters you can work with: contingency, or retained. Contingency-based recruiters will source candidates for you, somewhat manage the introduction and first conversation, and charge you a percentage of the candidate’s yearly salary as a fee. The contingency model is typically success-based, so no matter how many candidates they may send your way, they only get paid when a candidate gets hired.

Retained recruiters typically charge a monthly fee, but spend a lot more time working with you to find the right candidate and spend additional time helping you directly manage the hiring process. Both models are expensive, but ultimately, the time they might save you is well worth it, depending on how specialized the roles are.

You should also use an Applicant Tracking System (ATS) to manage this process. An ATS typically helps you post job listings, manage candidates and the interview feedback process, and everything else until the offer letter. You can think of it as a CRM for people who go through your interview process, but instead of selling software, you’re selling them the idea of working for your company.

There are plenty of ATS providers out there, but I typically recommend Ashby.

Once you’ve had a few resumes to review from all of your herculean sourcing efforts and inbound interest, it’s time to ensure you have your interview process squared away so you can invite candidates to go through it.

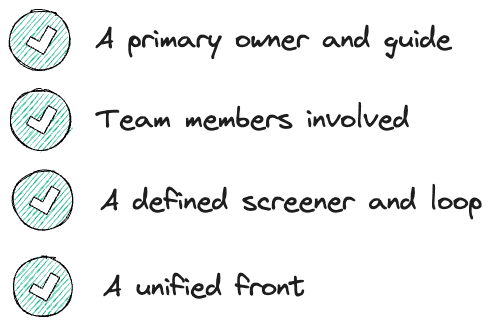

Before inviting a candidate to interview, you should have several things defined:

Define an Owner

You’ll need four things, and the first is a primary owner and guide. This will either be the person managing the hiring process or the person managing the candidate if they are hired at the company. This person is responsible for staying in constant contact with the candidate and setting up all of the necessary interviews with team members.

Giving a candidate communication whiplash, where one person tells them one thing and another tells them a different thing, is a great way to lose them, and ghosting them is even worse. Don’t do that—their time is just as valuable as yours.

Assemble Your Crew

The second thing you’ll need to do is define which team members will be involved in the interview process. Interviewing is an art that involves proving to the candidate that you’re going to be a great team to work with by engaging in conversation with them, and receiving the right amount of information to evaluate whether or not they’ll be a good fit for the company.

If you’re uncertain about a team member’s ability to interview someone, don’t include them in the process. Each team member interviewing a candidate should be able to provide detailed notes about their conversation and evaluate them on a numerical scale that you set for your process to rate candidates.

One golden rule: if they’re not a hell yes, they won’t be a great fit.

Have a Formula

This process's third and most important part is defining your screener interview and loop. Your screener conversation should be a 15-30 minute conversation led by the primary owner with the candidate to gauge their interest, ask them about their resume and experience, and see if they pass some of the qualifications you’ve listed in the job description. It also allows the candidate to mention discrepancies between their resume and your job description.

One thing I liked doing during a screener was applying the airport test. If my flight was delayed for 6-8 hours, would I want to be stuck in an airport with this person? It’s a great way to see if the candidate would make a good culture fit for your startup. If they pass the screener, the primary owner then coordinates with the candidate and team of interviewers to set up a block of time to conduct a loop.

I try to discourage teams from having a million scattered conversations with the candidate. Instead, schedule a block of time to loop the candidate through several of your interviewers. Depending on seniority, we would typically use a 1.5-2.5 hour block to loop the candidate through 3-5 interviews. This way, instead of 30-minute blocks all over their schedule, the candidate can talk to each team member during the same session and doesn’t need to break up their schedule in a strange way.

These interviews typically cover the candidate’s job history in the first interview, followed by several focus interviews covering very specific subject areas to test their aptitude and see if they meet the requirements for the role.

Follow the Script

Returning to the previous point about your team, the fourth part of the process involves having a united front. You want to ensure that when the candidate asks about the company, the answers are consistent, and you also want to ensure that every team member knows what they are responsible for during the interview process.

Your job is to sell the company as much as it is to evaluate a candidate. They’re taking on risk to work for your startup, and there are plenty of other opportunities that would come their way coupled with better short-term compensation and security. Don’t just turn it into an interrogation - tell them about your vision and ambitions, and have your team talk about their experiences working for the company.

Finally, if a candidate makes it this far, one thing I encourage companies to do is have a paid assignment. If you ask someone to do work for you, regardless of the outcome, pay them. By doing so, you're showing them that you value their time.

Assignments should take the candidate no more than 2-4 hours for a standard role or 3-5 hours if it’s a leadership role. It should have a very well-defined objective while not guiding the candidate towards any means of getting there. You’re seeing how they approach a problem statement you give them, and evaluating their solution based on their route to get there.

We’ve now reached the references and offer stage. If candidates pass the assignment step, ask them for 2-3 references. It’s good to optimize for people they’ve worked with prior or collaborated with in the past. You should expect the references to want to guide the conversation towards the most flattering things they could say about the candidate.

However, your job is to ask them about the bad times. Ask them about when the candidate had to make a tough decision or struggled with something—you’ll learn more about the candidate's human side rather than their pure work side. Frame it as wanting to learn more about how to best work with them and adapt to their working style from a position of aid - not scorn. You’ll learn more by doing this instead of asking about their working relationship, which will be completely biased.

When speaking to a reference, you should tell them about the company, your vision, and how well the candidate did during the interview process. If they’ve reached the reference stage, they know they did well enough to do so, and it shouldn’t be a mystery.

If these all check out, it’s time to give a candidate a formal offer in writing.

I don’t have much to say about job offers other than the following: if you really want to hire a candidate, do what you can to close them. At this stage, this is a sale more than a recruitment process. Make them a competitive offer and give them room to counter if you expect they will.

Don’t get offended by a counter-offer (unless it’s completely unreasonable); you can even mention to a candidate that you use software to benchmark compensation so they don’t have unrealistic expectations. Also, don’t get offended if they tell you they have another offer they’re considering (to use as leverage), or if they gracefully turn down the offer.

You might do the same thing in their shoes - I turned down an offer for a job at an amazing company to start SpruceID instead.

Just wanted to include a few closing notes here:

Don’t be afraid to fire individuals having issues at your startup. There isn’t time for rehabilitation beyond 30-day reevaluation periods if a new hire struggles (bar outside emergency or medical issue). Additionally, they eventually become a drag on the rest of your team. You’ll know firing someone was the right decision if there’s zero or positive impact the next day on productivity.

Also, you don’t have time for interns at this stage. Your time is valuable, and you don’t have the time to train them. They typically require much more management unless they can accomplish an extremely well-scoped project during their internship that requires minimal oversight. Also, pay your interns - experience doesn’t pay their rent.

Now, go off and hire for your next role.