Untitled post

Our instinctive reaction to new and revolutionary technology is often fear of consequences that we cannot predict. But if we can rein in our instincts and conquer our fears, maybe we can master of the technology.

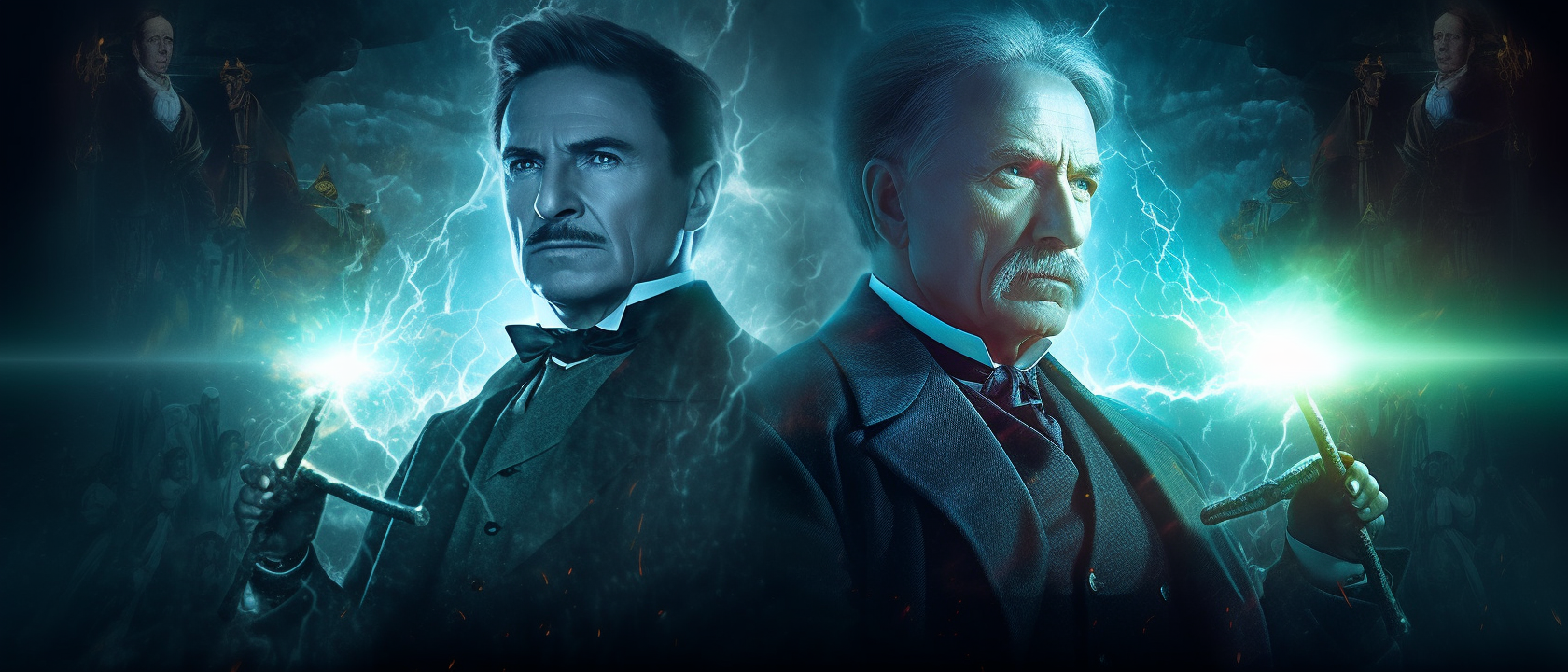

This is a link-enhanced version of an article that first appeared in the Mint. You can read the original here. The header image of this post was generated by Midjourney.

In the late 19th century, much of the Western world was gripped by an electrifying rivalry between two of the greatest minds of the time. It came to be called the ‘War of the Currents,’ and pitted Thomas Edison, the world’s most prolific inventor, against his arch-nemesis, Nikola Tesla, a brilliant Croat polyglot who, ironically, became the recipient of the Edison Medal from American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

A Standard for Electricity

Their feud was over which electrical system should power the world: alternating (AC) or direct (DC) current. Edison argued that DC current was far easier to store (an important consideration, but perhaps too personal, given that he was invested in the promise held out by electric vehicles). It was also far better for use in small applications with delicate electronics and thin wires. AC was fatal for anything that used electronics, which were soon rendered non-functional by the momentary loss of power that occurred each time the current changed direction.

Tesla, on the other hand, argued that it was precisely because AC reversed direction a specified number of times per second that it was easy to transport over long distances, which meant that noisy, polluting generation stations could be established far away from cities where the electricity was consumed. The high voltages at which it would be transported was not as big a problem as it was being made out to be, since it was quite easy to use a transformer to convert AC down to lower voltages as required.

The stakes were high, as the winner would get to electrify the nation—and eventually the world.

Conquering Fear

And so they both went all out to come out on top. Edison orchestrated demonstrations to prove the dangers of AC, going so far as to publicly electrocute a number of different animals to show how dangerous it was to have AC current flowing through wires in your home. Despite being an avowed opponent of capital punishment, he recommended its use for the electrocution of those on death row, arguing that the guarantee of death that AC provided was a humane alternative to the other methods then in vogue.

People were understandably rattled. Most of them saw electricity as a mysterious, invisible force of nature that they knew, from anecdotal and personal experience, caused severe shocks and devastating fires. They feared it viscerally.

But despite this rocky start, in time we learnt to harness the power of electricity. We came to understand that the problem lay not with electricity itself, but our ability to understand and control it. And once we figured that out, we put in place appropriate measures to handle it safely, so we could use it for our benefit. As a result, it ceased to be something we feared and went on to become one of humanity’s most important technological advances.

Today, electricity powers our very existence. Nothing we do is possible without it—from the massive industries that are the basis of the modern economy to the gadgets that guide us in our daily lives.

The fear we feel when we are confronted with a new technology for the very first time is not unusual. It is a common human reaction to a powerful threat that we do not fully understand but can sense. This primal response to the unknown is a survival mechanism hardwired into our brains that alerts us to potential threats and enables us to take evasive action for our own survival. When technology presents itself in this manner— displaying the many ways in which it can harm us—our instinct is to run, and, unless we are able to take control of this visceral reaction, we will forever deny ourselves all this new technology has to offer.

Harnessing AI

We find ourselves in a similar situation today.

After the initial excitement over artificial intelligence (AI), all I can hear from those around me is fear and consternation at how it will harm us, transforming humanity in ways we will not be able to fully control. There are fears of job displacement—a worry that, unlike in the past when technology replaced physical tasks performed by human workers, this time round machines were coming for the work we do with our minds. Concerns about how these new technologies will interfere with our perceptions of the truth, blurring the lines between fact and fiction till no one knows what is real and what is not.

These fears are not entirely unfounded. Artificial intelligence has the potential, as we have already seen, to do all this and more. We have seen how it can fill gullible minds with questionable facts. While we might suspect them to be untrue, we also find that they are next to impossible to distinguish from actual facts. The technology can be used to make decisions about us that, if not managed carefully, could perpetuate prejudices and biases that we would never have thought machines capable of. And there is always the fear that the technology we have created potentially conceals an artificial general intelligence with capabilities far superior to what we believed it can do.

The fear of the unknown is a natural human response. New powerful technologies easily provoke it. But history has shown us that, if we harness it properly, this fear can be a catalyst for progress. Just as we learnt to harness electricity, turning it into a force for good, we can tame AI and use it to power the future of human society.

Rather than being paralysed with fear, we need to learn to understand and control AI. After all, the future is not something that just happens. It is something we need to shape.