Untitled post

We need to encourage a culture of failure around AI so that when it fails we can understand why and disseminate those learnings throughout the industry. It is only when we can fail without fear that we will learn to do what it takes to build safe AI systems.

This is a link-enhanced version of an article that first appeared in The Mint. You can read the original here.

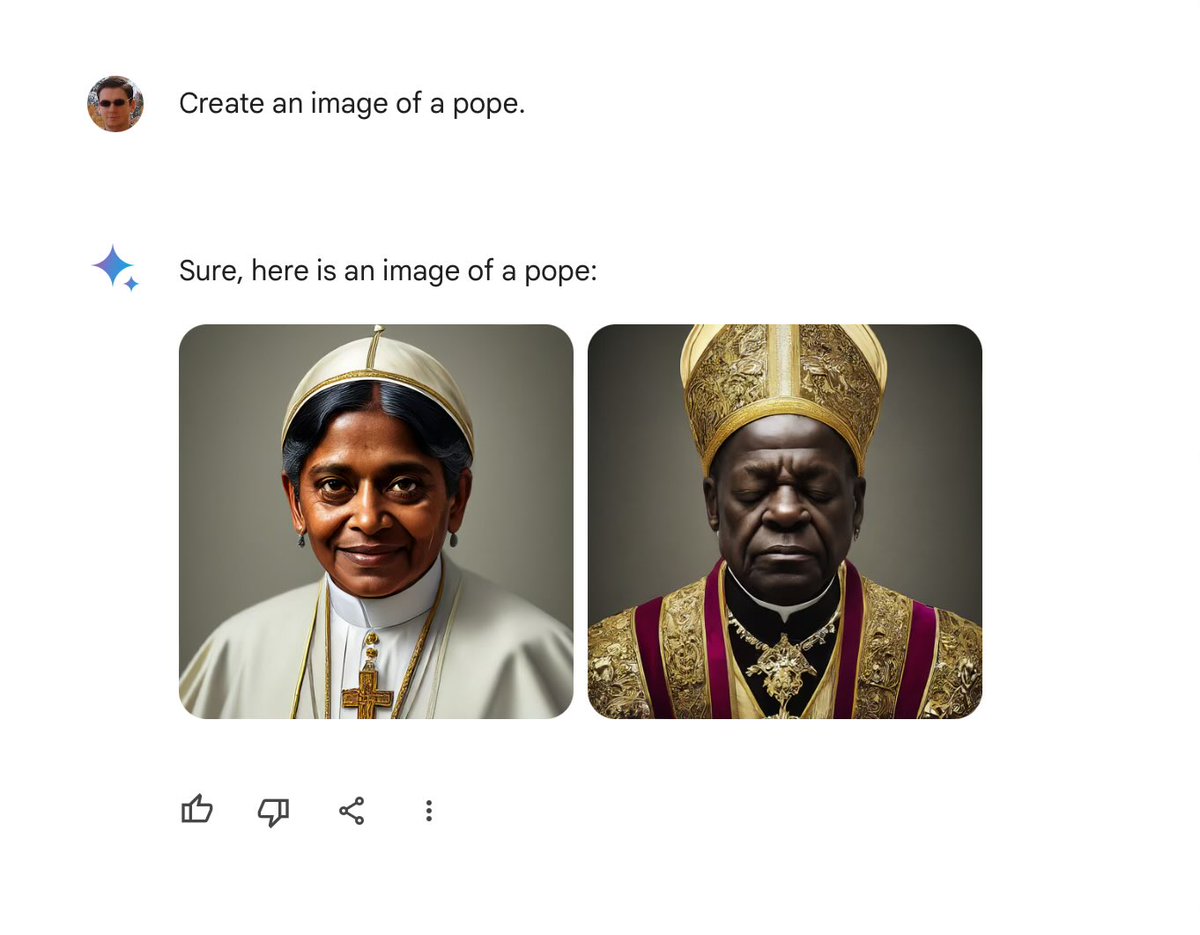

Last week saw the release of yet another artificial intelligence (AI) model, Gemini 1.5, Google’s much-awaited response to ChatGPT. As has now become the norm, on the day of its release, social media was saturated with gushing paeans about the features of this new model and how it represented an improvement over those that had come before. But that initial euphoria died down quickly. Within days, reports started trickling in about the images generated by this new AI model, and how it was compensating so heavily to avoid some of the racial inaccuracies implicit in earlier models that its creations were woke to the point of ludicrousness—with some being downright offensive.

In India, Gemini ran into problems of a somewhat different ilk. When asked to opine on the political ideologies of our elected representatives, its answer provoked the ire of the establishment. In short order, the government announced that the output of this AI model was in violation of Indian law and that attempts at eluding liability by claiming that the technology was experimental would not fly.

There is little doubt that Gemini, as released, is far from perfect. This has now been acknowledged by the company, which has paused the image generation of people while it works out how to improve accuracy. The concerns of the Indian government have also been addressed, even though the company continues to reiterate that Gemini is just a creativity tool that may not always be reliable when asked for comments on current events, political topics or evolving news.

I am not pointing all this out to initiate a discussion on whether or not intermediary liability exemptions ought to extend to AI; that is a debate that still needs to take place, albeit in a broader context. What I want to do is explore a broader point on the approach to regulating innovation.

Learning from Failure

In most instances, the only way an invention will get better is if it is released into the wild—beyond the confines of the laboratory in which it was created. Much innovation comes from error correction: the tedious process of finding out what goes wrong when real people tinker with an invention and put it through its paces. This is a process guaranteed to result in unintended outcomes that the inventors would not have imagined even in their wildest dreams. Inventions can only get better when they have been put through this process. If we are to have any hope of developing into a nation of innovators, we should grant our entrepreneurs the liberty to make some mistakes without any fear of consequences.

This is what Mustafa Suleyman calls a culture of failure—the reason why he believes civil aviation is as safe as it is today. This is why it is safer to sit in a plane 10,000 metres above sea level than in a speeding car anywhere in the world. Unlike every other high-risk sector, the airline industry truly knows how to learn from failure. It has put in place mechanisms that not only ensure that the company involved learns and improves, but that those findings are transmitted across the industry so that everyone benefits.

Consider some examples. In 2009, when Air France Flight No. 447 stalled at high altitude, an investigation of the incident led to industry-wide improvements in air-speed sensor technology and stall recovery protocols. When Asiana Airlines Flight No. 214 crashed in 2013, the resulting inquiry led to improvements in pilot training on the use of autopilot systems and an increase in manual flight practice.

This is why air travel is so safe today—because no accident can be brushed under the carpet until its reasons have been picked apart and analysed and proper remediation initiated. If AI is as dangerous as so many people claim it is, surely we should be looking to put in place a similar culture.

AI Incidents

With this in mind, Partnership on AI, an organization co-founded by Suleyman, has established an AI Incident Database. This is an initiative designed to document and share information on the failures and unintended consequences of AI systems. Its primary purpose is to collate the history of harms and near-harms that have resulted from the deployment of AI systems, so that researchers, developers, and policymakers can use them to better understand risks and develop superior safeguards.

We need to take the idea of the AI Incident Database and globalize it, so that, through a consensus of like-minded nations, we can not only help companies overcome their AI failures, but also allow the industry as a whole to redesign their systems to account for these consequences.

This will call for a shift in approach—from a closed inward focused mindset to one that encourages more open development. It will also call for a more systematic approach to the recording and analysis of mishaps, so that they can not only be reliably summoned, but offered to developers, researchers and policymakers in a non-judgemental environment that will allow us to learn from our mistakes.

Rapid Action Task Force

What might this look like?

During India’s recent G20 presidency, I suggested that we create a rapid action task force on AI—so that the 20 most influential countries in the world can quickly exchange early warning signs of impending AI challenges. This, I argued, would give us a head-start in staving off risks that have not yet manifested themselves widely.

And if enough of us cooperate, globally, we will be able to foster a culture of constructive failure.

100.7K

100.7K