Virtual Power Plants

Everyone says we need to embrace renewable energy to address the challenges of climate change. But integrating variable supplies of electricity into our current grid is easier said than done. One way to do that might be to virtualise our power plants.

This is a link-enhanced version of an article that first appeared in the Mint. You can read the original here.

While I am not knowledgeable enough to opine on all the various complexities of climate change, I have on occasion reflected in this column on the role that technology can play in easing our transition to renewables. I have often commented on how we might need to make fundamental changes in the way our energy infrastructure is designed.

Renewable energy is notoriously fickle. All it takes for supply to be disrupted is slightly overcast skies or a subtle change in weather that becalms the winds. This means that we will only be able to use the full potential of our renewable energy resources when have in place effective storage solutions to address this intermittency. While some might argue (legitimately, I should add) that it is the responsibility of energy companies to make the required arrangements for it, there is only so much they will be able to do in the short time we have left. We need more creative solutions.

In an earlier column, I suggested that we should think about using vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies so that we can take advantage of the rapidly increasing number of electric vehicles (EVs) in the country. Most EVs have battery packs large enough to not only take us to work and back, but also have energy left over to supply the average household with the 15-20 kWh of power it needs in a day. All we need to do is install a bi-directional charging unit so that EVs recharge their batteries whenever electricity is cheap and readily available, and, when it is not, offer this stored energy as an alternate source of cheap household power.

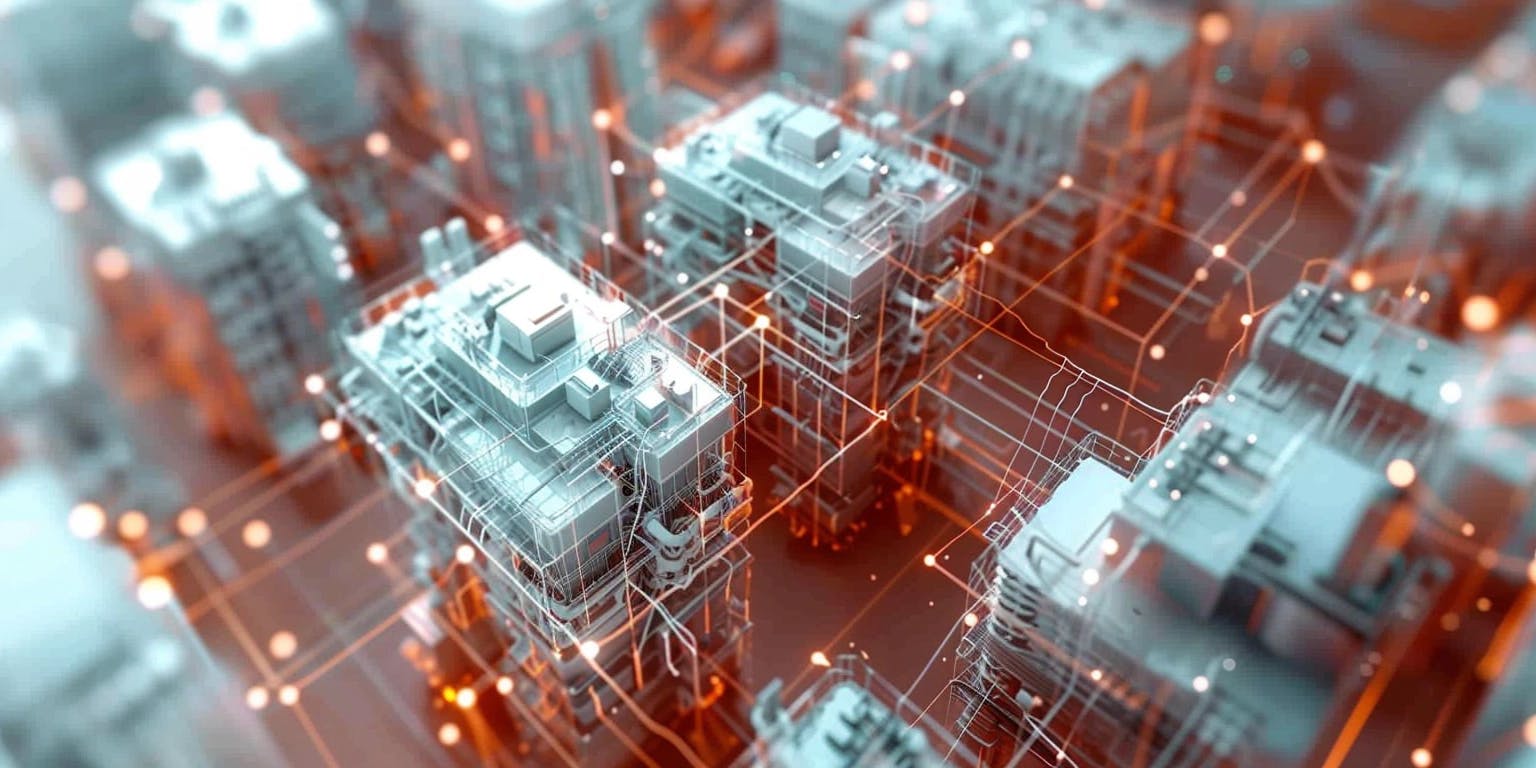

If we can set up this sort of intelligent energy infrastructure in our homes, I see no reason why we cannot integrate multiple such personal systems into a single decentralized storage network that entire neighbourhoods—and even small cities—can use. Designed thoughtfully, this sort of distributed storage infrastructure could eventually stabilize the grid against the sorts of fluctuations that we currently rely on ‘peaker plants’ to address. Key to this would be the strategic deployment of network technology solutions that are capable of integrating all these diverse and distributed energy sources into one unified and flexible power supply system, which, through real-time data analytics and active monitoring, will be able to efficiently aggregate available energy resources to guarantee reliable supply.

But why just stop at improving supply-side efficiencies? Almost all the appliances in our homes and offices come equipped with sensors and many of them have network connectivity that allow us to interact with them. If we can use these features to coordinate the way in which they consume power, or at the very least ensure that their operations are synchronized with the intermittent supply we receive from our renewable energy sources, we should be able to significantly improve our energy efficiencies.

This will call for a fundamental re-ordering of the way things currently work. Today we generate power centrally in massive industrial facilities that supply it to the grid for subsequent distribution to our homes and offices. It is thanks to this arrangement that we can always be sure that we will have energy available on tap whenever we need it.

If we are to transition away from this system to the renewables-centric model that I described above, we will have to re-imagine what we believe a power plant ought to be. The only way we will be able to dynamically balance variable demand with intermittent supply is if we can build a system that is completely virtual from end to end.

Virtual Power Plants (VPP) are designed to be able to intelligently coordinate energy demand with variable supply. They do so by managing power-consuming appliances like smart thermostats, electric vehicle chargers and home energy management systems on one hand, while at the same time augmenting supply through a combination of distributed storage and available sources of renewable energy on the other. For instance, for peak-demand times, VPPs will be able to temporarily reduce the power that these devices consume while drawing on energy that may be available from various distributed storage units at their disposal.

In order for this approach of using Virtual Power Plants to be effective, we will need to put in place a common technology infrastructure that all stakeholders in the energy space will have to commit themselves to and implement, so that their systems can communicate with each other seamlessly. Done right, we will be able to efficiently manage energy flows across a range of diverse and distributed energy resources, grid operators and consumers in a highly effective way.

The most efficient way to do this would be to have in place a set of protocols that individual stakeholders can design their systems to conform to. For instance, we could build on key features of the Beckn protocol, which has featured previously in this column, and design a set of open and interoperable protocols that stakeholders can use to coordinate their various actions across the energy ecosystem in real time.

At scale, this will allow us to efficiently implement real-time energy management in a world of variable supply and demand. Without this sort of automated coordination between the various elements of our energy ecosystem, our ambitions of using renewable sources to avert a climate crisis may remain a pipe dream.