Sensemaking Networks: Project Introduction

Incorporating science social media into the scientific process

I’m excited to start this blog as I begin a new chapter as an Entrepreneur-In-Residence (EIR) at the Astera Institute! Astera is launching the visionary EIR program to catalyze the upgrading of our aging infrastructure for science publishing and communication.

In this post I'll tell you about my planned residency project, which I'll be developing on along with partners at Astera, Common Sensemakers and beyond (we're still in the process of team formation).

The project is called Sensemaking Networks, an upgrade of social media designed for scientists and other knowledge workers, combining the strengths of AI-augmented social media networks with decentralized semantic nanopublishing, to radically enhance information flow as well as participants’ agency and data sovereignty.

This first post will focus more on the "why" of the project (background and motivation), and in future posts we'll focus more on the "what" and "how" of implementation.

Sensemaking as a missing layer from the scientific record

As we and others have previously made the case for, science social media is far from just an idle diversion for scientists while they aren’t writing papers. Rather, it merits treatment as an integral part of the scientific process: science social media is part of the sensemaking layer of science that helps us to collaboratively communicate, contextualize, curate and assess research. The sensemaking layer improves the inclusivity of science, bringing the broader public into direct contact and participation in discourse around science. However, this blurring of the lines between scientists and "citizen scientists" is unfortunately part of the reason this layer gets ignored. Another reason is the "messiness" of the sensemaking layer, which can include any kind of knowledge shared by people as they engage with scientific research, such as annotations, reviews and social media commentary. More generally, we tend to ignore what's hard to measure, and sensemaking is a complex process where knowledge hasn’t yet crystallized into a polished paper:

And yet, we ignore the sensemaking layer at our peril: Science has not taken ownership of the sensemaking layer, and as a result, it is siloed and fragmented across many platforms, with profiteering publishers vying for control of researchers’ data as part of their transformation into data tracking and analytics conglomerates.

These corporations’ operations are often at odds with basic scientific values such as transparency and free access to knowledge. More importantly perhaps, researchers are overwhelmed with information, yet lack access to the people, tools and data that will help them collectively make sense of research and advance science.

So what are the problems with the existing infrastructure, and how does our project fit into the landscape of existing solutions?

Limitations of existing science communication infrastructure

Sensemaking Networks are designed to address three interrelated limitations of traditional (and non-traditional) science publishing and communication:

Lack of support for diverse publishing formats and scales.

Feedback loops are too long and opaque, and publications’ reach is poor.

Non-traditional publications are siloed and fragmented across many apps and formats.

Let's look at each of these in detail:

Lack of support for diverse publishing formats and scales. In traditional publishing, the basic unit of knowledge is a paper, a format that has changed surprisingly little over the past hundreds of years, given that since papers, we’ve also invented computers and the internet. Thankfully, in recent years people have been expanding the concept of publishing to include a far wider range of activities, both in terms of formats as well as scale. The Nanopublications project is a great example of this nascent trend: as the name implies, nanopublications are aimed at representing very small units of knowledge - typically corresponding to a sentence or two in natural language. What makes nanopublications especially interesting is that they employ Semantic Web principles to represent publications as small knowledge graphs, which are great for representing information in an unambiguous, machine-actionable manner. Nanopublications are also diverse: they can express virtually any kind of knowledge, from a relation between a gene and a disease, to an opinion about a scientific paper or a blog post. More later on why nanopublications are so cool and potentially transformative.

Feedback loops are too long and opaque, and publications’ reach is poor. Traditional publishing is a slow back-and-forth between authors and reviewers, taking months or even years from submission to publication. The review itself is usually hidden from the public, creating a process that is opaque (other researchers in the field could have learned from the review) and non-inclusive (only 3 randomly selected reviewers can participate, why not others?). Finally, traditional methods do little to improve the reach of publications; most research is lost in the deluge of new papers, perhaps never to be found by its intended audience. These shortcomings of traditional publishing help explain why science social media (shorthand for the use of social media for science communication) has become so popular: scientists can disseminate their research on social media (e.g., Twitter, Bluesky, etc) and receive immediate feedback. Social media’s public nature invites broad participation, and algorithmic feeds coupled with social graphs greatly improve reach: retweets by “science influencers” can lead to millions of views. A key insight we'll be returning to throughout is that, in many ways, researchers are already nanopublishing on social media, but just don’t know it yet. What if Twitter was real academic work?

Non-traditional publications are siloed and fragmented across many apps and formats. While the Open Science movement has significantly improved access to traditional publications (papers), non-traditional publication is a wild west of non-interoperating apps and formats. As noted above, science social media functions de facto as an important nanopublishing venue where all manner of valuable knowledge is shared. In many cases, commercial platforms like Twitter enclose this data as part of their business model, directly hindering open science. Even on more open social platforms such as Mastodon or Bluesky, the lack of standard formats and support for semantic publishing makes it difficult to effectively aggregate, filter and index data at scale and across platforms.

Enter Sensemaking Networks

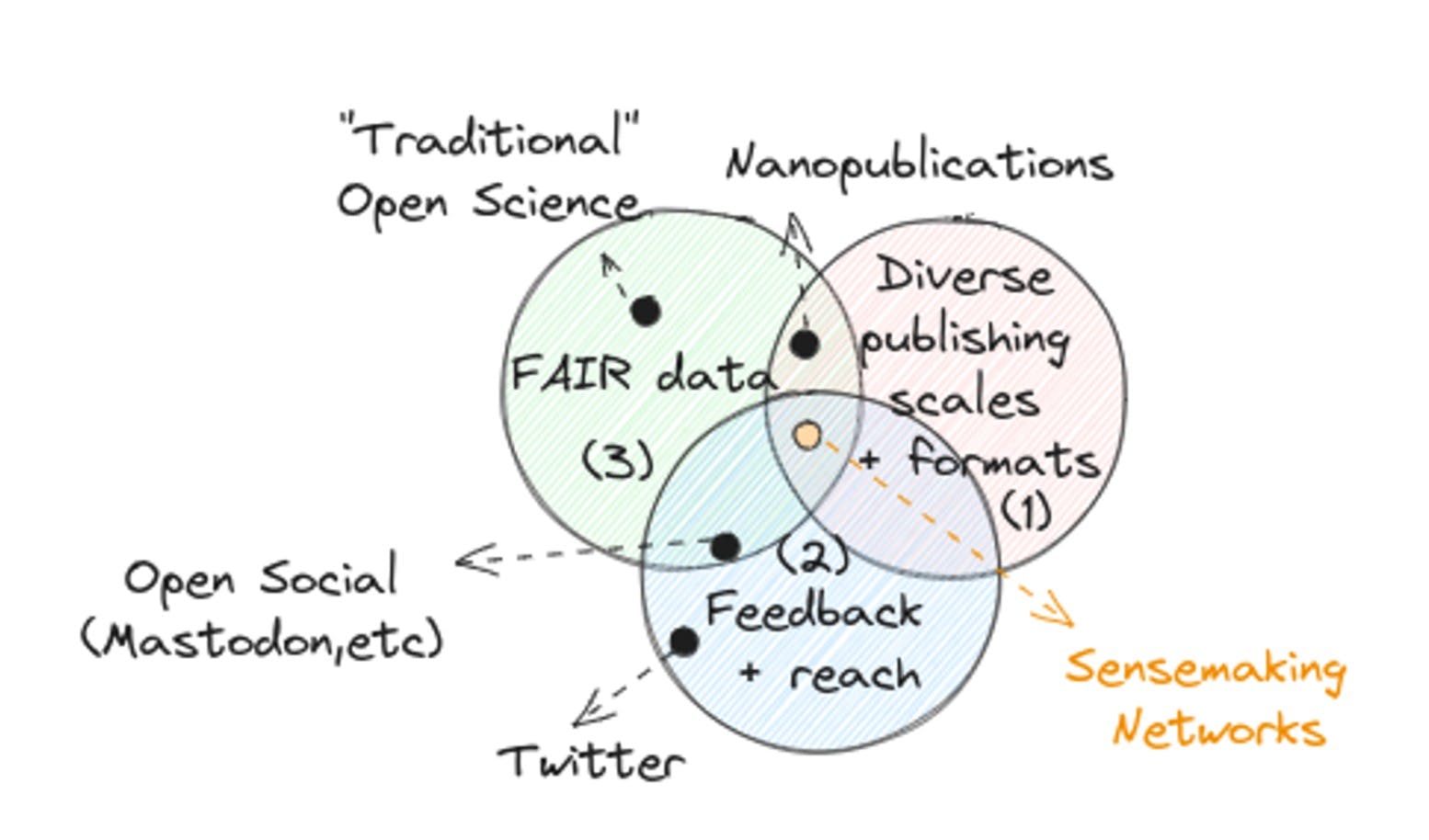

We envision Sensemaking Networks as federated/decentralized Twitter-style social networks where posts are nanopublications, and data is open and FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable). As shown in the Venn diagram below, our approach aims to draw on the best of social media networks in terms of feedback and reach, while addressing their limitations of siloed data and restricted publishing expressivity.

Nanopublications are great for expressing diverse kinds of knowledge, but can be clunky to create and lack the “aliveness” of social networks. By embedding nanopublications in social networks we can enhance their discoverability and encourage their broader adoption by researchers who want to not only publish, but also engage with other researchers and the broader public. AI will play multiple key roles in Sensemaking Networks, both to make semantic publishing as easy as posting on regular social media, and also for improving reach and feedback, for example by connecting people with relevant content and other researchers.

In the next post we'll dive into our project plan and more concrete implementation details, stay tuned! Please subscribe to this blog if you want to stay updated about project developments, and potential contribution or job opportunities. Also feel free to reach out at ronen@astera.org if you want to chat about this more!

That's it for now! 🚀

2

2

Love it! Looking forward to watching this develop. Seems we have a lot to discuss re: semantic publishing, such as Lens Protocol, and what JournoDAO is doing with "PermaPress" involving Ethereum Attestation Service. I also tagged DeSciWorld in my twitter share, cause they're working on a similar project involving an LLM-integrated engrammatic knowledge graph.

Glad you liked it, and thanks for the heads up! The journalism direction sounds super relevant, this piece may be interesting to you - https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2019.1651665 Anyway, let's chat more about this :)

An intro post about Ronen Tamari's new project at Astera Institute about scientific semantic publishing! Very important ideas discussed here, regarding scientific sensemaking and composable nanopublications.