Composable Minds

Memory invocation techniques without written texts

The following text has been presented as a lecture performace at IMPACT23 - Ecologies of Attention Symposium, Pact Zollverein (Essen, D) in 2023. It is also an edited and extended transcription of a previous talk called Songlines, presented online at Trafó House of Contemporary Arts as part of (H)earring Series #19 in 2021 April 20. Revised & edited in June, 2023

Greetings, welcome everyone. In the next half hour I will talk about the artistic methods, experiments, research that are important for me in the recent years as an individual creator and as a member of the Binaura artist collective. The topic of this lecture can be traced back deep in time, and in fact we will go back in time and investigate a few inspirational cultural and technological cases that are defining these areas. In the first part I will talk about the methods of algorithmic thinking. In the second part, I will talk a bit about artificial intelligence, machines that we consider intelligent, responsive environments, and the fusion of software and our everyday lives.

“A monk’s day begins with cleaning. We sweep the temple grounds and gardens and polish the temple building. We don’t do this because it’s dirty or messy. We sweep dust to remove our worldly desires. We scrub dirt to free ourselves of attachments. [...] This is the power of routine.” - Shoukei Matsumoto, Soji

So let's have a closer look on the mechanism that we can call a routine, a ritual which is a repetitive, iterative thinking and planning process. These attempts can be found in our everyday lives, for example if someone has a sort of routine of waking up, drinking a coffee, then starting up the day... It can be just as an important ritual, such as a sacral or religious, emphasized repetitive sequence. The above quote clarifies this idea a bit: there is no need for any over-complication. The text is from Shoukei Matsumoto and it is about how a monk's day starts: cleaning the ground of the temple, the gardens and the different objects around. These activities are made in order to achieve a deepened mental focus. Regarding to routine, I would like to introduce a personal experiment from 2018 which is called HackPact. This project consists of a series of exercises, which has a tradition that originates from several years back, that was initiated by creative programmers. A hackpact is a month long interval where each day is an opportunity to investigate a problem in a form of code writing. A simple code helps framing and processing the problem: separate, small experiments with different topics. An important thing here is, that since we are talking about rituals, we will have rules, and our procedures are bounded to these rules. They are set up by the creator as creative constraints. These constraints are fundamental part of the creative process: they reduce possibilities which are useful from the aspects of curiosity, exploration regarding to a specific problem. They act as catalyzers or extrapolators. They amplify components, if the available tools are narrow, their usage can lead to new ways of improvisation in order to present an idea.

In the case of my practice, these constrains consist of the number of colors used (black, white and red where action happens), reduced number of forms (lines, circles and a few geometric objects), or the avoidance of using prerecorded sound samples. It is instead based on simple sound synthesis, basically frequency modulation. It needs to work online in realtime, which leads to many tech related compromises and opens up ways for learning novel things during the implementation process. Hackpact originates from live coding, which means to modify the code on the fly while it is running and changes are interpreted in a live and direct way. The concept had many incarnations: Codevember, 100 days of code, hackpacts, etc. These movements started in the beginning of the 2000s. The manifest here defines that sound should affect the graphical appearance, and vice versa. It then becomes a visual sonic instrument, where those two entities are inseparable.

Speaking of practice, I really like the example brought forward by Ian Bogost in his book "Play Anything". He says that anything can be converted into a playground in the life of humans. A nice example is if someone is trying to leave their home and can't find their keys, then the whole house can be turned into a gameplay where the goal is to find the keys, and the house becomes the game environment. The different areas in the rooms become game objects and elements.

“The arena, the card-table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, the court of justice, etc., are all in form and function play-grounds, i.e., forbidden spots, isolated, hedged round, hallowed, within which special rules obtain. All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart.” - Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens

This playground is an area, that is defined by the rules of the game. This area can be the house, this can be a chess board, this can be an abstract process that we saw in the case of a hackpact, where the rules are quite strictly defined. Everything that is not included in this playground, is the rest of the world, that does not take part in the game. It is not necessarily a spatial or physical distinction. If we throw a ball into a net, then it is only an act, where we take an object and throw it somewhere. It doesn't really have a meaning in itself. But if the rules reinterpret this action, and this will have a meaning in an abstract system, such as receiving some points for it, then this action will be placed inside the playground. The border that is between the ordinary world and the inner playground, like a membrane around a cell or a zone, is called the Magic Circle (term by Dutch historian Johan Huizinga). The exposed events are happening inside the magic circle, based on the predefined rules. Everything that is outside of the circle is not part of the game. It might be interesting to add, that these zones can be treated as temporary worlds. They exist temporarily within the outer reality. We construct these in order to provide a scene for performing.

In order to make these temporary zones move we need to record processes, stories, narratives, that are connected to them. These narratives can be interpreted in many ways. There are ways to store creature mythologies, or there are ways to record rules of a game on paper where we define a sequence of game turns. We are using different tools in order to store these information through our cultural history. These tools are also called mnemonic, or memory devices. One such great and well known tool for this is writing. Through writing we can formalize and share knowledge in a very effective way. Snippets of knowledge can be reproduced in exact and consequent forms. Apart of writing, there are many other tools, such as the so called Memory Palaces that were used among indigenous people. These are tactile devices made of pearls and shells, that highlight important artefacts in different stories. They shared information and knowledge without writing among several generations. In fact, there is a similar method called songlines, where people were using their natural environment as visual landmarks for knowledge sharing areas. There, the different elements in the landscape were functioning as different knowledge fragments. While walking on the land, they were singing songs, melodies and sharing stories belonging to different landscapes. An interesting aspect of memory is that it is interconnected with space. Moving in space itself, transporting something from one place to another has always been a very important role in distributing values among our society. Navigation itself is a key element of accessing memories. An interesting example of mnemonic navigation can be found in the oceanic transportation of the Polynesian islands.

They were using special devices for tracing the routes, called stick charts. They were using different sticks to create an abstract map of the territory where they recorded the water streams, wind directions and the waves that were identical to specific areas in relation to the islands. The islands were highlighted with pearls and directions of streams were indicated with longer, rotated rods. What is escpecially surprising with these objects is that they didn't bring them along their journeys, since they wouldn't be able to use them, while struggling with the coordination and maintaining boat functionalities. So these objects in fact act as mnemonic devices. They observed the possible ways ahead of the journey and decided the strategy in advance of the realization of the action according to area-specific variables. When they were travelling along the actual routes, they were recalling the forms from their memories. The charts acted as symbolic links to specific decisions. This way we can treat these stickcharts as code systems, that has been studied by the navigators and their decisions and acts were interpreted based on those instructions.

"Imagine that you could pass through two doors at once. It's inconceivable, yet fungi do it all the time. When faced with a forked path, fungal hyphae don't have to choose one or the other. They can branch and take both routes." - Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life

I find the term Unfolding Intelligence quite appropriate and it seems to catch quite well the nature of that transformation that happens when a so called intelligent or conscious reaction happens or a decision process can be found in reality*. This act unfolds into and over something. It is manifesting. The term Unfolding Intelligence includes the fact that intelligence is an active process that happens through a series of events where if the causalities are occurring together accordingly, then a constructive transformation evolves. These are all active processes, where a structured, productive and creative force or energy emerges. Intelligence itself is introduced in a beautiful, poetic manner in the recent book of Merlin Sheldrake, called Entangled Life. The book is a very interesting introduction into the world of fungi and fungal networks, called mycelium that surround us within our biological environment. An important note here is that the human attitude towards artificial intelligence is very human centered, or anthropomorphic. Which means we have a body that contains the brain, which is responsible for the thoughts and decisions as a central organ. If we are navigating through a space, then when we have to cross a door, we have to choose which door we would like to cross, since we can only walk through on one door only at a time. In the case of mycelium, since it has a branching structure, and it is colonizing space in an omnidirectional manner, it can turn over into myriad ways simultanely and find its path to go along. This thought might indicate that maybe there is not always a central brain which is only responsible for the decisions of intelligence, but it can really work in a decentralized way, where decisions are made by different, independent cooperating agents. We can see this in mycelium network dynamics, or the colonies of ants, swarm based animal navigation, emergent systems in nature that can be hardly described through central, serial logic such as the simultane rotation of swarming fish that is faster than the information that they could pass over between them individually.

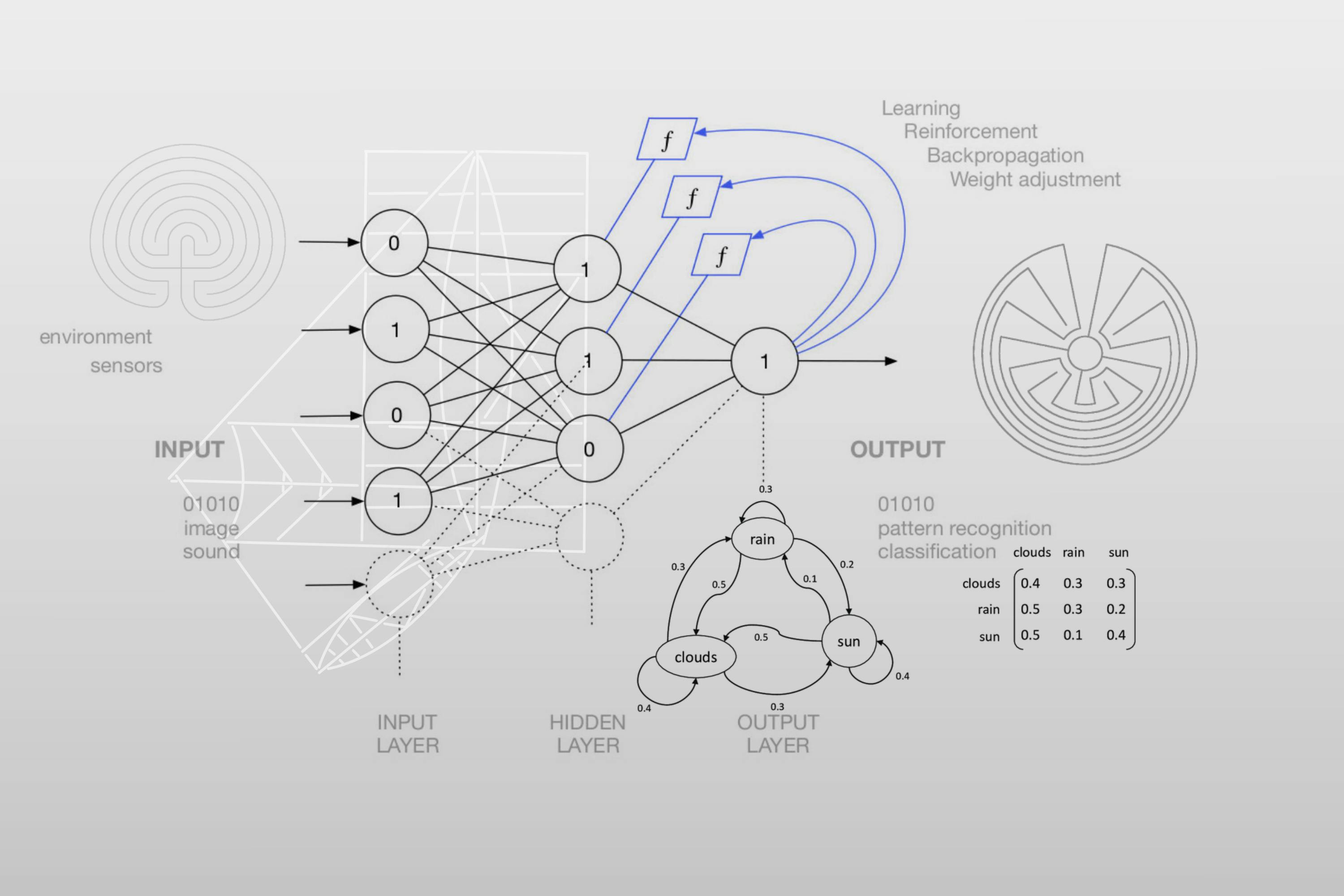

Regarding to spatial movements and decision making, since ancient times there are structures that can illustrate them in a very convenient way, that are called mazes and labyrinths. A navigator makes decisions while trying to find the relevant path over a labyrinth. The decisions are made in a sequence after each other, which leads to the unfolding of decision trees. The tree archetype itself is also used as knowledge organizing model. A labyrinth can be transformed into a decision tree, if we connect the decision making events with a separate coordinate system. This is a reason why visualizations are really powerful when it comes to understanding complex ideas and knowledge structures without sequential writing systems. Instead of sequenced chunks of information, visualization exemplifies the underlying structures. These labyrinths and their corresponding decision trees are accurate demonstrations of the way we navigate through mental states. The weight of these decisions that a network makes, can be studied in different structures. The underlying model is basically a graph system. A Markov chain, or Markov Graph is a set of weighted decision trees.

On this particular example, weather condition changes can be simulated based on random probabilities. It has nothing to do with our real environment, it is only a model where the decisions have been weighted. The weather can be rainy, cloudy or sunny. The arrows indicate the directions of the transitions between the different states. The numbers indicate the probability of such transitions. From sun to rain, there is a 0.1 (10 percent) probability to change, also, from rain to sun, there is a 0.2 (20 percent) probability to change back to the sunny state. There are many analyses and predictive systems that are based on similar random probability state machines. For example, musical note transitions within melodies can be identical and different that can observed in a Bach fugue, compared to a romantic musical piece. So this can be used for very general purposes. These weighted Markov chains present nicely the results when we variegate chance, probability and randomness with algorithmic thinking and create novel structures from them. My work Songlines* introduces a kind of learning process that can be studied in a playful way by the user. That learning process is built on environmental parameters and the agents inhabiting it.

Such environment can be a labyrinth where we can only turn left or right in order to navigate forward and the agent is a being that is navigating in that labyrinth. For this being, the whole world means only this labyrinth. Its explicit knowledge and experience of the world is only turning decisions between walls. In this world, there are no other elements that it perceives. On one hand, to build up routines, reactions, human relationships, gameplay itself is essential, on the other hand, this can be applied to the area of artificial systems. A typical game context provides an extremely useful set and setting for the act of learning. Positive and negative rewards and feedbacks from the environment can lead to an effective navigation throughout the environment. Later on, the agent can start improvising and find novel solutions to problems. This type of learning process in games is also called Reinforcement Learning. It is another, scalable paradigm in network graphs: as opposed to manually constructed symbolic states that can be found in Markov models, the states of each node (perceptron) in a neural network are composed of abstract weights on the atomic level, between zero and one. Their meaning depends on their role in the patterns of the network, similarly to how neurons function in a brain. This method is used in autonomous driving systems, balancing robots and other physical phenomena, where physical experience can not be exchanged with pre-recorded historical data. This way agents can figure out the rules of a system in an unsupervised manner: it would be too difficult to hardwire those decision trees into those robots and physical actors by traditional programming routines, since there are too complex scenarios to consider in real world environment, from lighting conditions to temperature anomalies, material qualities, raining and so on. Games, computational and generative media can be used to simulate ecological models including the complex, global ecosystems. Clusters of climate change, including many different problematic causalities can be simulated and extrapolated through predictive, speculative and future related scenarios. In many cases they can augment regular, everyday thinking via testing associative models that can be simulated in a compressed time interval so we don't have to wait years to test long term causalities in reality. It seems these advanced networks become more and more embedded in the way we humans tend to think and act.

“The choices we are faced with today are especially important because digital technology so dramatically increases the ‘space of the possible’ that it includes the potential for machines that possess knowledge and will eventually want to make choices of their own.” - Albert Wenger, World After Capital

*: my interactive artwork Songlines (with identical name as the original lecture performance) has been exhibited at the Generative Unfoldings exhibition as part of the Unfolding Intelligence Symposium, organized by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Bogost, Ian: Play Anything (2016)

Bostock, Mike: Visualizing Algorithms (2014)

Bunz, Mercedes: The Force of Communication (2021)

Chang, Y Alenda: Playing Nature (2019)

Eco, Umberto: The Search for the Perfect Language (1995)

Huizinga, Johan: Homo Ludens (1955)

Matsumoto, Shoukei: A Monk's Guide to a Clean House and Mind (2018)

Penny, Simon: Making Sense (2018)

Sheldrake, Merlin: Entangled Life (2020)

Wenger, Albert: World After Capital (2021)

Wickers, Ben & McDowell, K.A (ed): Atlas of Anomalous AI (2021)

mnemonic devices, cognitive mapping and artificial intelligence - https://paragraph.xyz/@stc/composable-minds my next article on @paragraph https://paragraph.xyz/@stc/composable-minds